Ridwan Oloyede and Victoria Adaramola

The Gambia has enacted the Personal Data Protection and Privacy Act, a landmark legislative milestone that formalises the country’s commitment to digital rights and data governance. This enactment follows the successful validation of the National Data Policy earlier in the year and marks the conclusion of a legislative process that had stalled for several years. With this development, the Gambia joins a growing list of African countries that have established robust legal frameworks to regulate the processing of personal data. The Act is comprehensive, structured around international best practices. It aims to balance the legitimate needs of government and businesses to process data with individuals' fundamental rights. Its core objectives include protecting individual privacy, ensuring lawful data processing, and establishing an independent oversight body to enforce compliance.

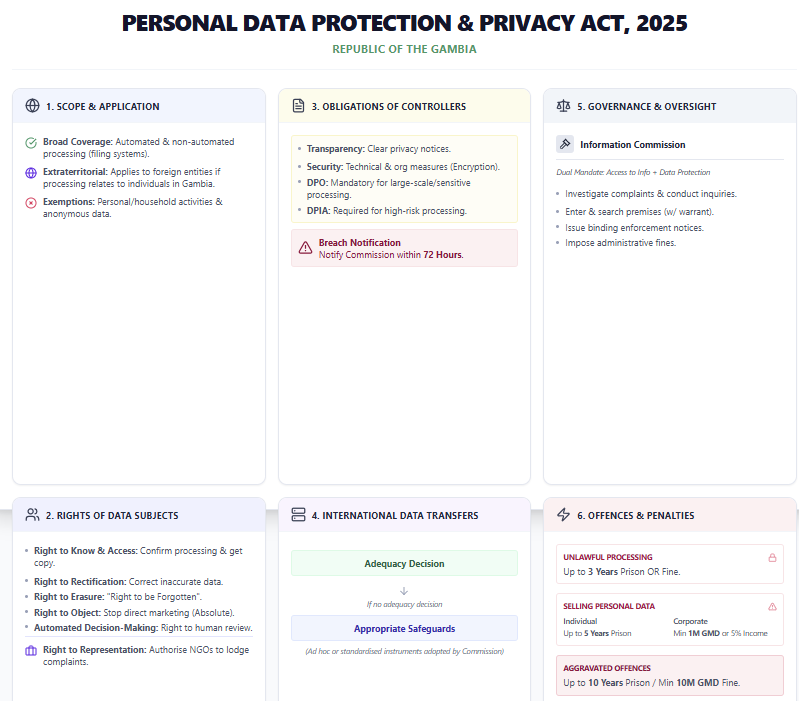

The Act applies broadly to the processing of personal data by both automated and non-automated means (where such data forms part of a filing system). Notably, it asserts extraterritorial jurisdiction, applying not only to controllers established in The Gambia but also to those outside the territory if their processing relates to individuals within the country. This ensures that foreign entities that process data subjects' data in the Gambia fall within the scope of this law. Exceptions are carved out for purely personal or household activities and for anonymous data, aligning with standard international exemptions.

The Act codifies the fundamental principles of data protection, creating a mandatory framework for all data processing activities. It stipulates that data must be processed fairly, transparently, and lawfully, ensuring that individuals are aware of how their information is used. Furthermore, data collection is subject to the purpose limitation, meaning it must be collected solely for explicit and legitimate purposes. To prevent over-collection, the Act enforces data minimisation, requiring that data be adequate and relevant to the specific purpose for which it is processed. Accuracy is also paramount, requiring controllers to maintain accurate, up-to-date data. Finally, the Act mandates that data be processed securely, maintaining its integrity and confidentiality against unauthorised access or loss.

It establishes seven lawful bases for processing, mirroring those in other data protection laws across the continent. Processing is lawful if it relies on consent, contract performance, legal obligation, vital interests, public task, or legitimate interest. Additionally, the Act provides a specific basis for processing carried out for archiving, public interest, scientific, or historical research, or statistical purposes, provided that appropriate safeguards are in place. The Act also addresses the repurposing of data, allowing for secondary use only after a compatibility assessment. When determining whether a new purpose is compatible with the original purpose, controllers must consider the relationship between the purposes, the context of collection, the nature of the data, the potential consequences for the data subject, and the existence of safeguards.

The Act imposes a stricter regime for the processing of sensitive personal data, including genetic and biometric data, as well as data revealing racial origin, political opinions, or health status. The processing of such sensitive data is generally prohibited unless the controller can identify a lawful basis and satisfy one of the specific conditions set out in the law. These conditions include explicit consent, obligations in the field of employment and social security, vital interests where the subject is physically incapable of consenting, or reasons of substantial public interest such as public health or national security.

The Act empowers individuals with a robust suite of digital rights, transforming them from passive subjects into active participants in the data economy.

The Act imposes rigorous accountability measures on organisations, extending beyond basic security to cover the entire governance of data processing.

Transparency: Controllers are obligated to act transparently. Under the Act, they must proactively provide data subjects with clear information regarding the controller's identity, the legal basis and purposes of processing, the categories of data, and the recipients of that data. This information must be provided at the time of collection or within a reasonable period if the data was obtained indirectly.

Processing Children's Data: The Act prioritises the protection of children, defined as persons under the age of 18. Controllers processing a child's data must prioritise the child's best interests and privacy. Specific safeguards are required for marketing or profiling directed at children. Furthermore, the lawful processing of a child's data generally requires parental or guardian consent, and all information directed at children must be in clear, plain language that they can easily understand.

Joint Controllers: When two or more controllers jointly determine the purposes and means of processing, they must clearly specify their respective compliance responsibilities. This arrangement must be made available to the data subject, who retains the right to exercise their rights against any joint controller.

Data Processing Contracts: The Act formalises the relationship between controllers and processors. Controllers must only use processors that provide sufficient guarantees of compliance. The Act requires that this relationship be governed by a contract or legal act that sets out the subject matter, duration, nature, and purpose of the processing. Crucially, processors may not engage a sub-processor without the controller's prior written authorisation.

Data Protection by Design and Default: Controllers are legally required to integrate data protection principles into their processing activities from the outset. The Act mandates that technical and organisational measures be designed to implement data protection principles effectively and to ensure that, by default, only personal data necessary for each specific purpose of the processing is processed.

Records of Processing Activities: To demonstrate compliance, both controllers and processors must maintain a written record of processing activities. The Act specifies that this record must contain details such as the purposes of processing, descriptions of data subjects and categories of personal data, and recipients of the data.

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIA): High-risk processing activities, such as profiling or large-scale surveillance, require a prior DPIA to identify and mitigate risks before processing begins.

Data Protection Officer (DPO): The designation of a DPO is mandatory for public authorities and organisations engaged in large-scale monitoring or processing of sensitive data.

Breach Notification: The Act sets a strict timeline for reporting breaches. Controllers must notify the Commission within 72 hours of becoming aware of a breach and must also notify affected data subjects without undue delay if there is a high risk to their rights.

The Act regulates the transfer of personal data to countries or international organisations outside The Gambia to ensure that the level of protection guaranteed by the Act is not undermined. The Act establishes a structured approach to these transfers. The primary mechanism for transfer is adequacy, where the receiving country or international organisation has a law that provides an appropriate level of protection. In the absence of such a law, transfers may proceed based on appropriate safeguards. These safeguards can be established through ad hoc or standardised instruments adopted by the Commission. The controller is responsible for assessing whether an appropriate level of protection exists, taking into account the nature of the data, the purpose of the transfer, and the recipient country's legal regime. Furthermore, the law requires the controller or processor to document the assessment of the appropriate safeguards or criteria that justify the transfer, thereby ensuring accountability. The Commission plays a supervisory role and must be involved in assessing whether the transfer criteria are met.

Rather than creating a new agency from scratch, the Act designates the Information Commission (established under the Access to Information Act, 2021) as the regulatory authority. This dual-mandate approach leverages existing institutional structures. To ensure robust enforcement, the Commission is granted independence and extensive powers, including the authority to investigate complaints and conduct separate inquiries; to enter and search premises with warrants; to impose administrative sanctions and monetary fines; and to issue binding enforcement notices.

The Act introduces a comprehensive sanctions regime that combines administrative penalties with severe criminal liability for specific violations. The Commission has the power to impose administrative sanctions, including corrective warnings, enforcement notices, bans on processing, and financial penalties calculated by the Commission. Beyond administrative measures, the Act criminalises serious misconduct. Unlawful processing of data for financial gain or to cause harm attracts a prison term of up to three years or a fine of not less than 500,000 Dalasis (approximately USD 6,854). The sale of personal data is treated with particular severity, carrying a penalty of up to five years imprisonment for individuals, while corporate bodies face fines of not less than 1 million Dalasis or 5% of their gross income. Aggravated offences, such as unlawfully selling data, can result in imprisonment of up to 10 years and fines of not less than 10 million Dalasis (approximately USD 137,089) for corporations. Overall, criminal fines under the Act are substantial, ranging from a minimum of 500,000 Dalasis for individuals to over 10 million Dalasis for corporate bodies. Furthermore, the Act criminalises the concealment of a security breach, with a potential two-year prison term, and the obstruction of the Commission’s investigation, with up to seven years' imprisonment.

For organisations operating in The Gambia, the transition from enactment to enforcement requires a proactive and structured approach. Compliance is not a one-time event but a continuous process that begins with establishing a robust privacy program framework. Organisations should start by mapping their data to understand what information they hold and why, which is essential for maintaining the Record of Processing Activities mandated by the Act. This framework must align with the Act's specific requirements, such as appointing a DPO (where necessary) and integrating data protection by design into new projects. Crucially, organisations must invest in comprehensive training and awareness programs to ensure that all staff—from IT to marketing—understand their new obligations, particularly regarding consent and data subject rights. Finally, a static policy is insufficient; organisations must establish a monitoring and testing program to regularly audit their controls, simulate breach responses (especially given the 72-hour reporting window), and ensure that their data protection measures remain effective and compliant over time.

The Personal Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2025, represents a significant leap forward for The Gambia's digital ecosystem. The Act lays the groundwork for trust in the digital economy by establishing clear rules, enforceable rights, and a regulator. The inclusion of progressive elements such as the right to NGO representation and the criminalisation of data sales and re-identification demonstrates legislative intent to address contemporary data challenges aggressively. However, success will depend on effective implementation. The Information Commission faces the dual challenge of regulating both Access to Information and Data Protection—two distinct, albeit related, mandates. Ensuring the Commission is adequately funded and staffed with technical experts will be crucial.