Ridwan Oloyede and Victoria Adaramola

Introduction

Angola has introduced a draft Artificial Intelligence (AI) law. While not the first on the continent, it joins a growing wave of proposed AI legislative efforts. Other countries, including Egypt, Ghana (albeit broadly on emerging technologies), Morocco, and Nigeria, have specific legislative proposals. Concurrently, countries including Kenya, Mauritius, Namibia, Uganda, and Zimbabwe have announced intentions or initiated discussions to develop similar legislative intervention. This review analyses the proposed AI bill and examines its critical intersection with the draft amendment to the Data Protection Act.

The bill proposes a comprehensive legal framework governing the development, supply, and use of AI in the country. Its structure is heavily influenced by contemporary international principles, particularly those of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the risk-based approach in the European Union's AI Act, which categorises AI systems based on their potential for harm. The bill's core objective is to navigate the dual challenge of modern technology regulation. It aims to actively promote and build a domestic AI industry to capture economic value and ensure technological sovereignty, while simultaneously establishing robust, human-centric safeguards to prevent the kinds of harms to fundamental rights, ensure public safety, and establish clear lines of responsibility for automated systems that are now a global concern.

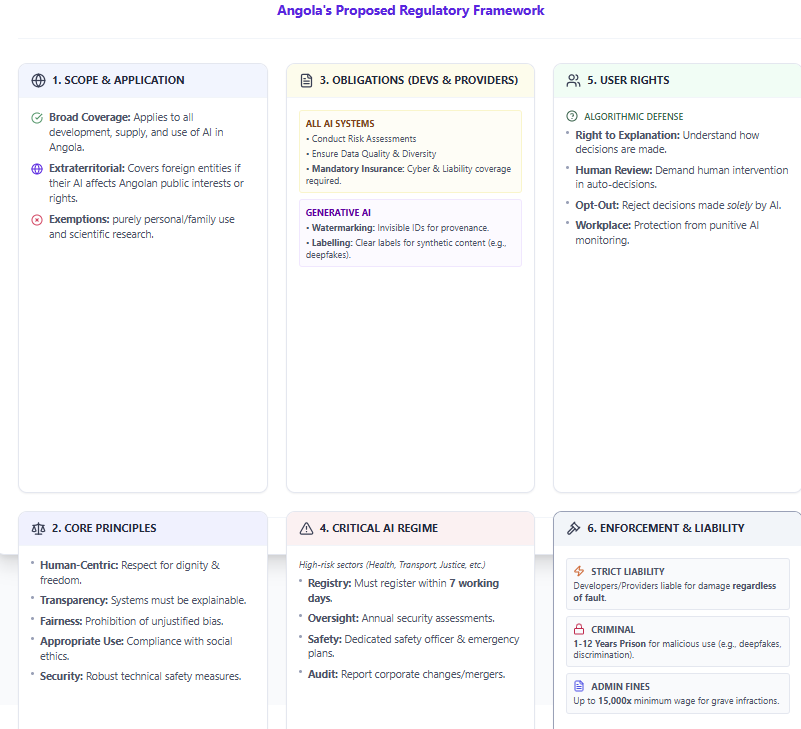

Scope and Application

The bill's scope is intentionally broad, covering all AI development, supply, and use activities conducted in Angola. More importantly, it asserts a strong extraterritorial jurisdiction, designed to capture global AI players. It covers activities conducted outside Angola that "affect the public interests, or the legitimate rights and interests of natural and legal persons domiciled in Angola". This implies that the regulated entities would be compelled to adapt their global systems to Angolan standards or risk facing penalties, a significant compliance consideration.

The bill explicitly excludes two areas: AI used by a natural person for purely "personal or family matters", similar to household exemptions under data protection laws, and activities related to "scientific research in AI," an exemption presumably intended to avoid stifling basic research and innovation at its earliest stages.

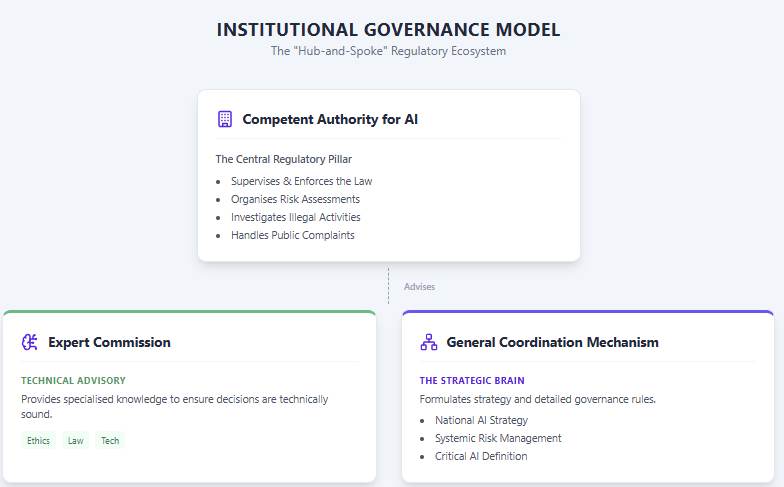

Regulatory Oversight and Governance Model

The bill will establish a new "competent authority for AI" as the central body responsible for regulating, supervising, and enforcing the law. This authority is the pillar of a multi-part governance model designed to create a flexible and informed regulatory posture. This structure avoids regulating in a vacuum; the General Coordination Mechanism (which will be led by the competent authority) acts as the strategic brain, tasked with formulating the national AI strategy, establishing systemic risk management, and creating the detailed rules for ethics, data labelling, and the governance of "Critical AI." To support this, an Expert Commission will be formed to provide the competent authority with essential technical, ethical, and legal advice, ensuring that regulatory decisions are informed by specialised, up-to-date knowledge. Finally, a "diversified coordination" approach encourages the active participation of industry organisations, academic institutions, and civil society in managing AI risks. Key functions of the competent authority include formulating technical standards, organising and reviewing risk assessments, investigating illegal activities, and handling public complaints.

Principles

The bill lays out the fundamental principles that must guide all AI activities, serving as an ethical and legal compass for developers and providers:

Promotion of AI Development

The bill dedicates an entire chapter to fostering a domestic AI ecosystem, signalling that this law targets economic development alongside regulation. The government commits to building and coordinating national computing infrastructure, promoting interoperability, and encouraging the use of public compute platforms, especially for SMEs. Crucially, this infrastructure must adhere to sustainable, low-carbon principles. Beyond hardware, the law supports the creation of high-quality public datasets and promotes a domestic open-source ecosystem, including platforms, communities, and clear licensing governance.

The law protects AI-related software, patents, and designs, while also addressing the complex issue of AI-generated content. It states that such content is protected under IP law, provided that the owner is a natural or legal person. The bill clarifies the associated rights and responsibilities, imposing a disclosure obligation on the user to declare if a work, invention, or creation was AI-generated. Furthermore, the law directly addresses ownership by setting a clear default: while an AI provider and user must agree on ownership, in the absence of such an agreement (or if it is ambiguous), all relevant rights are conferred upon the user.

One of the bill's most significant provisions creates a "reasonable use" exception for training AI models. This exempts developers from paying remuneration or seeking permission to use third-party IP-protected data if the training use is "different from the original purpose... and does not affect the normal use of the data or unreasonably harm" the owner's interests. Aiming to lower the barrier to entry for domestic developers who may lack the proprietary data troves of large multinational tech firms, this provision directly addresses the central tension between the need for massive datasets and the constraints of intellectual property law. It provides a legal safeguard for data scraping for training purposes, provided the data source is "clearly identified." However, the ambiguity of the term "unreasonably harm" will likely become a critical issue in future legal disputes between AI developers and content creators.

Key Obligations for Developers and Providers

The law distinguishes between AI developers (those who build systems) and AI providers (those who supply them to users), often applying distinct or shared obligations to both.

General Obligations

"Critical AI" Regime

The bill introduces a high-risk category designated as "Critical AI". This risk-based tiering enables the regulator to concentrate its most intensive resources on applications that pose the greatest threat to society. Instead of applying a single, one-size-fits-all rule, the law imposes proportionate burdens. This category is defined by its potential impact, and includes:

Providers and developers of Critical AI are subject to a much stricter and more costly set of obligations, including:

Special Regimes for AI Application

The bill creates specific, hard-coded rules for high-stakes sectors, demonstrating a clear awareness of where AI poses the most immediate societal risks. These rules establish guardrails by limiting AI's autonomy in critical decision-making.

User Rights

The bill creates a strong set of rights for individuals interacting with AI systems:

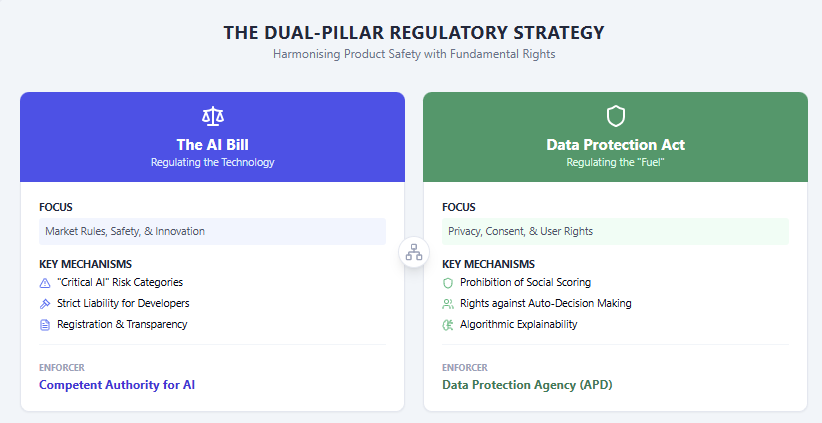

Intersection with the Draft Amendment to the Data Protection Act

The AI Bill does not operate in isolation; it is clearly designed to work in tandem with Angola's (draft) amendment to the Data Protection Act (DPA). The DPA introduces a specific chapter on "Processing of Personal Data by Artificial Intelligence Systems," which complements the AI Bill by providing a robust, data-centric layer of regulation. This dual-framework approach is a sophisticated regulatory strategy.

Key provisions from the DPA that intersect with the AI Bill include:

This dual-framework strategy is comprehensive: the AI Bill governs the technology as a product (focusing on market rules, safety, innovation, and high-risk applications), while the DPA governs the personal data used as fuel for that technology (focusing on privacy, consent, and user rights against data-driven harms). For example, the DPA's explicit ban on 'social scoring' provides a clear ethical boundary that the more general AI Bill benefits from.

Enforcement and Liability Regime

The bill introduces a dynamic, multi-layered liability and enforcement framework.

The law distinguishes between "Simple Infractions," such as failure to conduct regular inspections, and "grave infractions," which include failure to register Critical AI, failure to report incidents, or the violation of user rights. Fines are tied to the national minimum wage, creating a scalable and inflation-proof penalty. For grave infractions, these fines can reach up to 7,500 times the national minimum salary for individuals and 15,000 times for legal entities. Additionally, the bill mandates severe accessory sanctions for grave infractions, including the forfeiture of equipment, the closure of establishments for up to two years, or the suspension of licenses.

Conclusion

Angola's proposed AI law is one of the most comprehensive and ambitious regulatory frameworks on the African continent to date. The bill aims to establish a foundation of trust for its digital future by combining a risk-based approach with strong, centralised oversight and a novel, powerful strict liability regime. The creation of a parallel set of AI-specific rules within the revised Data Protection Act demonstrates a sophisticated, dual-pillar strategy to regulate both the technology itself and its data-driven implications. The explicit protections for users against automated decisions, the promotion of a domestic open-source ecosystem, and the imposition of severe criminal penalties for malicious use are particularly noteworthy.

The primary challenge, however, will be implementation. The success of this dual framework hinges on the ability of the new "competent authority for AI" and the Data Protection Agency to coordinate effectively and avoid jurisdictional disputes. Both bodies will need to rapidly build deep technical, legal, and ethical expertise to supervise a complex and rapidly evolving technology, from registering "Critical AI" and defining the precise legal boundaries of "reasonable use" of data to enforcing a strict liability regime that will undoubtedly be tested in court the moment it is enacted.